In the context of our seminar “Social Movements and Prefigurative Politics” we had the possibility to prepare a scientific video about a social movement of our choice. In our group, we soon found a topic everybody was interested in: the sharing economy. As there are several approaches a sharing economy can embrace, like car sharing, sharing of household devices or flat share, we must focus on one sharing activity that is foodsharing. A main reason for that was that foodsharing is a social movement that everybody can participate in, independent from gender, age, social role and so on. In addition, it affects everyone, because everybody needs food regularly. During our research we found out that there is a foodsharing spot at the Ruhr-University Bochum (RUB) and we decided to investigate foodsharing at the RUB regarding to prefigurative politics. Our research question is: Does the foodsharing activity at the RUB fit to the characteristics of prefigurative politics?

To answer this, we interviewed different people that are involved in foodsharing activities at the university. In sum, we interviewed eleven persons. Four of them were randomly chosen students we asked about foodsharing, three of them were students that participate in food sharing, one student was from the AStA that supports the foodsharing activities and two persons were from foodsharing e.V., a nationwide food sharing organization.

In the following, the idea of foodsharing, how it is realized at the RUB and the concept of prefigurative politics will be explained. Afterwards, an analysis of foodsharing activities at the RUB in relation to characteristics of prefigurative politics will be given.

The idea of foodsharing

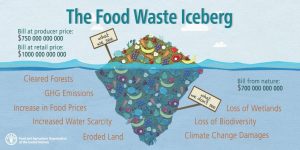

Being an inherent part of our lives, food is not only irremissible to survive, but also connected to cultural and societal practices (see Ganglbauer et al. 2014: 2). While in affluent societies food is an everyday matter of course, worldwide 800 million people suffer from hunger and two billion from malnutrition (Welthungerhilfe: Hunger). At the same time, every year one third of global food production for human consumption is lost or wasted (FAO: Save Food) and nearly 30 % of the world’s agricultural land is currently occupied to produce food that is ultimately never consumed (FAO 2016: 37). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), saving one fourth of this food would feed 870 million hungry people (FAO: Save Food). Among social and economic impacts, with being responsible for eight percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, food loss or waste is an environmental problem and would be, if a country, the third biggest emitter after China and the United States of America (see FAO 2015: 1).

While food loss takes place in the beginning of the supply chain, thus at the production and postharvest, food waste occurs at the end of the chain at the retail and consumer level. In industrial countries 40 % of losses happen at these levels (FAO: Save Food). Hence, habits and behaviour patterns of retailers and consumers have a great impact on saving food.

Figure 1: The Food Waste Iceberg. Source: fao.org.

The initiative of foodsharing provides an approach to create a world without wasting food. Launched in 2012, foodsharing is a German association that nationwide organises the sharing of food. Regional volunteers collect food at cooperating stores and bring it to foodsharing places that are open to the public or share it in other ways. “What matters is that food is “saved”, that is, consumed instead of being wasted” (Chies 2017: 4 ff.).

Foodsharing at the RUB

At the RUB, there is a foodsharing spot between the Kulturcafé and the AStA offices that persists of a fridge and a shelf. Members of foodsharing e.V. come twice a week to fill them with food from cooperating stores like supermarkets and bakeries. Additionally, everyone can bring food that is left. The food can be consumed by everybody for free. The AStA supports the foodsharing activity with calling attention to it, for instance via Facebook posts.

Figure 2: The foodsharing spot at the Ruhr-University Bochum. Source: own picture.

While interviewing students of the RUB about the foodsharing, we found out that students have an idea of what it is but do not know about the foodsharing spot at the university.

“I heard it [foodsharing] is when caterers have food left and share it with others.”

“I don’t know that much [about foodsharing], but I think it is about sharing food that is nearly extended, that you can spend.”

“Foodsharing is familiar to me. It is about not wasting food that is left in a household and is still eatable and further shared. It is a good approach that I support.”

The concept of prefigurative politics

Prefigurative politics experiments with alternative ways of living their initiators seek to implement as standards by exemplifying a lifestyle to others through one’s own life. Darcy K. Leach from Bradley University states that the

“term prefigurative politics refers to a political orientation based on the premise that the ends a social movement achieves are fundamentally shaped by the means it employs, and that movements should therefore do their best to choose means that embody or “prefigure” the kind of society they want to bring about” (Leach 2013: 1).

With providing an alternative way of living and institutions prefigurative politics is a form of a social movement with the aim to create a new society not by revolution, but within existing structures. Strategically, prefigurative politics is “based on a principle of direct action, of directly implementing the changes one seeks, rather than asking others to make the changes on one’s behalf” (Leach 2013: 1).

For Luke Yates, “[t]he concept [of prefigurative politics] (…) refers to the attempted construction of alternative or utopian social relations in the present” (Yates 2015: 1). According to him, salient for prefiguration is a combination of experimental building alternatives in everyday or mobilisation-related activities, the way practices are performed, meaning an equity in means and ends, an orientation towards future and make activities political relevant (see Yates 2015: 13 ff.). To evaluate the political logic of prefiguration, Yates identified five identifiable processes as a compound of prefigurative politics: experimentation, the circulation of political perspectives, the production of new norms and conduct, material consolidation, and diffusion (see Yates 2015: 4).

Five social processes of prefigurative politics

To answer the research question, foodsharing at the RUB will be analysed regarding five social processes of prefigurative politics provided by Yates (see Yates 2015: 13 ff.). Previously, who is involved in foodsharing at the RUB must be clear. A case study of the foodsharing community by Ganglbauer et al. states that community members of foodsharing have different roles and interact in various ways (see Ganglbauer et al. 2014: 9). Chies confirms that with identifying three roles in the foodsharing movement; foodsavers that collect food, store coordinators who manage partnerships with stores and ambassadors who officially represent foodsharing at a regional level (see Chies 2017: 6). In the case of foodsharing at the RUB, there is, among foodsavers, another group involved which persists of student that participate. The different groups possess different levels of engagement and responsibility, and thereby different roles that are acknowledged in the following analysis.

1. Experimentation

The first process Yates identifies is experimentation. Seeking to change the status quo, activists start changing practices in their own everyday life in a reflected and conscious way. In addition, there is experimentation in political mobilisation (see Yates 2015: 13).

While some students that participate in foodsharing at the RUB come to the spot several times a week, others visit it more spontaneous, but nevertheless regularly.

“I know about the foodsharing from (…) the AStA. Since then I come regularly, like two or three times a week, and I think it is one of the most meaningful ideas.”

“I heard about the foodsharing program via Facebook. I walk by and look if there is something, it is more spontaneous and not something planned. (…) I am really often at the university and can look every day if here is something.”

Students that participate in foodsharing change their habits at the university. With altering practices and reflecting them foodsharing at the RUB involves experimentation in everyday practices of participating students. The foodsharing community experiments with everyday practices pictured on the Facebook page and the website of the foodsharing association:

“(…) the Facebook page provided a platform for people to form a community of interest, passion and activism around the issue of food waste and sharing food. It enabled people to mobilise and to act as a ‚global-issue-based‘ community, to seed new local communities, while Foodsharing.de enabled people to form a local community of practical action to hand over food between the members” (Ganglbauer et al., 2014: 9).

Moreover, with a focus on not-wasting food, free riding is accepted. Rombach and Bitsch conclude that, “due to the absence of classical free riding, the organizational activities show the underlying characteristics of a social movement, fostering change” (Rombach and Bitsch, 2015: 5). An example for experimentation in political mobilisation is the initiative of a foodsharing spot at Wacken Open Air festival in August 2018 (see picture below). With experiments in everyday life of students and foodsavers as well as in political mobilisation, foodsharing at the RUB includes the process of experimentation.

Figure 3: Foodsharing spot at Wacken Open Air. Source: facebook.com/foodsharing.

2. Perspectives

The second process is called “circulation of political perspectives”, meaning that “prefigurative groups host and develop and critique political perspectives, ideas and social movement frames” (Yates 2015: 14). Yates means thereby also the organisation of seminars, debates, conferences and the like.

Participating students at the RUB are not a group of its own, but rather a “sub-group” of foodsharing e.V. as a superior organisation. As Ganglbauer et al. state, the foodsharing association mainly provides “organisational means and technological resources to enable the emergence of this community” (Ganglbauer et al., 2017: 9). With progressing social perspectives, ideas, social movement frames and organizing events like a foodsharing festival (see foodsharing.de) this association possesses nationwide groups that organize foodsharing regionally and bring food to foodsharing spots like the one at the university. Due to their regional divisions, circulation of political perspectives takes mainly place through social media. Ganglbauer et al. found out that

“the Facebook group of the community acts as a forum for direct encouragement (…) [t]hat is accompanied by tensions and hot debates about political and cultural implications of food and waste practices that characterise this community” (Ganglbauer et al. 2014: 9).

Discussing possibilities of a systemic change or question the systemic impacts of foodsharing (see Ganglbauer et al., 2014, 9) within the community political perspectives circulate and foodsharing at the RUB fulfils the process through activities of the connection to the foodsharing community.

Figure 4: Logo of the foodsharing festival. Source: foodsharing-festival.org.

3. Conduct

According to Yates, prefiguration involves establishing new collective norms. These norms develop through the first two processes – experimental practices and alternative political perspectives. New patterns are debated, discussed and decided by a prefigurative group that shape their collective conduct into daily routines and further develops and improves the ‘experiment’ (see Yates 2015:14).

As above, this process does not fully take place within the rather loose group of participating students at the RUB, but therefore within the group of activists, respectively foodsavers, that belong to the foodsharing association and supply the foodsharing spot with its essentials. According to Ganglbauer et al.

“[t]hey could effect change, both by empowering individuals to act locally and form local food exchange groups, and empowering people more generally, even if they didn’t have a local group, to change thinking, to be more aware and to act politically through giving information, stimulating discussions, pro-active appeals and establishing public discourses” (Ganglbauer et al., 2017: 9).

Debating about experimental practices and alternative political perspectives in the Facebook group, the process of conduct takes place in the inherently connected activist group, where it establishes new collective norms, and therefore is part of the foodsharing activities at the RUB.

4. Consolidation

Usually, the first three processes are consolidated in a material environment or social order. This consolidation “tends to be limited, temporary, miniaturised or curtailed – the occasions when it is not are examples of prefigurative social movement success” (Yates 2015: 14). As the foodsharing movement consists of many regional groups, there is merely little common material environment to be shaped. Indeed, there is a social order that promotes a certain conduct. This conduct is adapted not only by activists of the foodsharing association, where the first quote is from, but also by participating students, as the second quote shows.

“We participate in foodsharing because of all the wasting. We try to save food. It is a question of cost and we want to show that it is all eatable – no one dies.”

“I found it really important like the whole movement of the foodsharing idea because we waste so much food. I really enjoyed knowing about the possibilities to just go and left the foods somewhere and to be certain that somebody else can use it (…) I feel like it is really appreciating the food much more and being aware of the wasting and the consumption of food.”

With providing a foodsharing place at the RUB a consolidation of the first three processes forming the fourth process takes places in a limited form at the single foodsharing spot. Nonetheless, the political message and symbolism of not wasting food is widespread, especially through regional foodsharing groups that possess a social order:

“Volunteering at Food Sharing requires identification with the organization, ideological motivation, and commitment. It requires an integration of these activities in the individuals’weekly routines. In addition, members must show efforts to obtain the status of volunteers who collect the food items, the so-called foodsavers” (Rombach and Bitsch 2015: 11).

5. Diffusion

The last progress of prefiguration refers to practices, orders, devices and perspectives that are demonstrated and diffused as prefigured alternatives beyond the present. With the aim to convince more people from alternative patterns of though and action, prefigurative groups communicate their message to the public for example via media, workshops, protests, and also on a private level in informal conversations (see Yates 2015: 14).

The social movement of foodsharing offers a high degree of diffusion. As a decentral organization with many regional locations, alternatives are demonstrated in a wide range. Generally, the association of foodsharing diffuses them alternatives via facebook and its website, but also through an own youtube channel called foodsharingTV (see youtube.de).

Figure 5: Explaining video of foodsharing. Source: youtube.de/foodsharingTV.

Information at the RUB is provided by hosting organizations, for example by the AStA that supports the foodsharing spot at the RUB, by activists that supplies the food and also by participants like students. The involved people at the university demonstrate and diffuse practices, orders, devices and perspectives and therefore prefigurative alternatives at the campus and beyond. While the association of foodsharing operates at a more public level of information, the foodsharing activity at the RUB is mainly diffused through private conservations between students. Hence, diffusion is a process that is not only met by the superior foodsharing organization, but also by the foodsharing activity at the RUB itself.

Figure 6: Facebook post of the AStA. Source: facebook.de/AStA.Bochum.

Conclusion

Taking interviews for scientific research was an exciting experience and also a challenge. Being more creative and free in the form of doing research, it was necessary to set appropriate questions and choose interviewees wisely. With taking interviews as a basis for the inquiry, a researcher has no influence on the content or intensity and has to deal with the given answers. So, this conclusion refers to the given information we were provided.

Foodsharing at the RUB does not represent one prefigurative group for itself, but belongs to a superior group that fulfils all five processes of prefiguration Yates defines The processes are fulfilled in different degrees; while the process of diffusion is high through such a nationwide organization, the process of consolidation, especially regarding a common material environment, is fulfilled at a limited level. Students that participate in foodsharing at the university are involved in prefigurative politics, but more as single parts of it than forming a group. They share food and therefore participate in the main activity the foodsharing activists, so-called foodsavers, advocate, but do not act as a group of its own that is promoting a certain kind of prefiguration. Foodsharing at the RUB misses in some parts a political dimension a prefigurative group of its own should provide according to Yates. Certainly, this dimension is given through the foodsharing activists that are involved in the university’s foodsharing as well as in the foodsharing community. Nonetheless, being an inherent part of the foodsharing movement, participating students are, together with foodsavers, also part of the movement and therefore part of prefiguration. As a conclusion, foodsharing at the RUB is a form of prefigurative politics.

A contribution from Katharina Hagemann

References

Chies, Bruno M. (2017): Turning food “waste” into a commons, The case of Foodsharing (Germany) and Solidarity Fridge (Sweden), https://www.iasc2017.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/chies.pdf.

Ganglbauer, Eva/Güldenpfennig, Florian/Fitzpatrick, Geraldine/Subasi, Özge (2014): Think globally, act locally: A case study of a free food sharing community and social networking, http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2531602.2531664.

Leach, Darcy K. (2013): Prefigurative Politics, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm167.

Rombach, Maike/Bitsch, Vera (2015): Food Movements in Germany: Slow Food, Food Sharing, and Dumpster Diving, in: International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, Volume 18 Issue 3, 2015.

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (Ed., cited as FAO) (2013): Food wastage footprint, Impact on Natural Resources, Summary Report. Internet: http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3347e/i3347e.pdf, visited on 17.09.2018.

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (cited as FAO): SAVE FOOD: Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction. Internet: http://www.fao.org/save-food/resources/keyfindings/en/, visited on 17.09.2018.

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (Ed., cited as FAO) (2015): Food wastage footprint and Climate Change. Internet: http://www.fao.org/3/a-bb144e.pdf, visited on 17.09.2018.

Welthungerhilfe: Hunger: Verbreitung, Ursachen & Folgen, Was genau ist Hunger? Welche Folgen hat Unterernährung? Wo herrscht am meisten Hunger? Internet: https://www.welthungerhilfe.de/hunger/, visited on 17.09.2018.

Yates, Luke (2015): Rethinking Prefiguration: Alternatives, Micropolitics and Goals in Social Movements, in: Social Movement Studies, Jg. 14, Nr. 1, S. 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2013.870883.